| |

| |

Permafrost threatened by rapid retreat of Arctic sea ice

10 June 2008

National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), Boulder, Colorado

The rate of climate warming over northern Alaska, Canada, and Russia could more than triple during periods of rapid sea ice loss, according to a new study led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The findings raise concerns about the thawing of permafrost, or permanently frozen soil, and the potential consequences for sensitive ecosystems, human infrastructure, and the release of additional greenhouse gases.

"Our study suggests that, if sea-ice continues to contract rapidly over the next several years, Arctic land warming and permafrost thaw are likely to accelerate," says lead author David Lawrence of NCAR. |

| |

|

| |

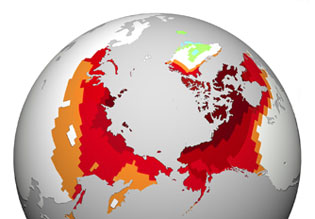

When sea ice is in rapid decline, the rate of predicted Arctic warming over land can more than triple. |

| |

|

| |

The study, by scientists from NCAR and the National Snow and Ice Data Center, will be published Friday in Geophysical Research Letters.

The research was spurred in part by events last summer, when the extent of Arctic sea ice shrank to more than 30 percent below average, setting a modern-day record.

From August to October last year, air temperatures over land in the western Arctic were also unusually warm, reaching more than 4°F (2°C) above the 1978-2006 average and raising the question of whether or not the unusually low sea-ice extent and warm land temperatures were related.

Previous simulation analysis suggested that a sustained period of rapid ice loss lasting roughly 5 to 10 years can occur when the ice thins enough.

During such an event, the simulation model revealed, the minimum sea-ice extent can drop by an area greater than the size of Alaska and Colorado combined. |

| |

|

|

| |

Below: Severe forest dieback giving way to bogs on Kruzof Island in southeast Alaska. These forests have not been disturbed in the last several thousand years, suggesting that dieback is a transitional stage toward dominance by the next stage in ecosystem succession. Photo Lee Klinger, Copyright © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

View larger image View larger image |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Above: The Trans-Alaska Pipeline north of Valdez. Alaska's infrastructure depends on permafrost staying frozen. The pipeline is above ground or in insulated ditches to keep the heat of the oil from thawing the permafrost it rests on. Permafrost thawing will have disastrous consequences for many parts of Alaska's built and natural environment. Photo Zhenya Gallon, Copyright © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

View larger image View larger image |

| |

|

| |

During episodes of rapid sea-ice loss, the rate of Arctic land warming is 3.5 times greater than the average 21st century warming rates predicted in global climate models. While this warming is largest over the ocean, the simulations suggest that it can penetrate as far as 900 miles inland.

The simulations also indicate that the warming acceleration during events is especially pronounced in autumn. The decade when a rapid sea-ice loss event occurs could see autumn temperatures warm by as much as 9°F (5°C) along the Arctic coasts of Russia, Alaska, and Canada.

Lawrence and his colleagues studied the influence of accelerated warming on permafrost, and found that in areas where permafrost is already at risk, such as central Alaska, a period of abrupt sea-ice loss could lead to rapid soil thaw.

When summer thaw extends more deeply than the next winterís freeze, a talik is formed, as a layer of permanently unfrozen soil sandwiched between the seasonally frozen layer above, and the perennially frozen layer below. A talik allows heat to build faster in the soil, hastening the long-term permafrost thawing. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Above: Bogs surrounding Hudson Bay, Canada. Computer models suggest that peatlands are especially sensitive to climate changes. As the globe heats up, they thaw, releasing huge amounts of methane and related gases.

Canada holds the world's second largest reserves of peat, after Siberia. Since methane levels in the atmosphere have globally increased erratically in recent years, sometimes by as much as one percent per year, tracing the origins and behavior of methane is particularly critical to understanding global warming. Photo: Lee Klinger, Copyright © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

View larger image View larger image

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Simulations by global climate models show that when sea ice is in rapid decline (top), the rate of predicted Arctic warming over land can more than triple.

View larger image View larger image |

| |

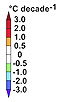

The image (above top) shows simulated autumn temperature trends during periods of rapid sea-ice loss, which can last for 5 to 10 years. The accelerated warming signal (ranging from red to dark red) reaches nearly 1,000 miles inland.

The image (above lower) shows the comparatively milder but still substantial warming rates associated with rising amounts of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere and moderate sea-ice retreat that is expected during the 21st century.

Most other parts of the globe (in white) still experience warming, but at a lower rate of less than 1°F (0.5°C) per decade.

Images: Steve Deyo Copyright © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) |

| |

|

| |

Potential impacts on greenhouse gases

Arctic soils are believed to hold 30 percent or more of all the carbon stored in soils worldwide.

Although researchers are uncertain what will happen to this carbon as soils warm and permafrost thaws, one possibility is that the thaw will initiate significant additional emissions of carbon dioxide or the more potent greenhouse gas, methane.

About a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere's land contains permafrost, defined as soil that remains below 32°F (0°C) for at least two years.

Recent warming has degraded large sections of permafrost, with pockets of soil collapsing as the ice within it melts. The results include buckled highways, destabilized houses, and "drunken forests" of trees that lean at wild angles.

"An important unresolved question is how the delicate balance of life in the Arctic will respond to such a rapid warming," Lawrence says. "Will we see, for example, accelerated coastal erosion, or increased methane emissions, or faster shrub encroachment into tundra regions if sea ice continues to retreat rapidly?"

The study sheds light on how interconnected the Arctic system is, says co-author Andrew Slater, a scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). "The loss of sea ice can trigger widespread changes that would be felt across the region." |

|

| |

|

| |

The greenhouse gas methane .....

Swamps and marshes emit significant amounts of the greenhouse gas methane. Although it is less prevalent than carbon dioxide, methane traps about 25 times more infrared radiation per molecule.

Methane is produced by many factors, including the cutting and burning of forests and grasslands, which causes soil microbes to alter their activity and release methane. It is also produced by termites, which release enough methane to contribute significantly to the total amount in the atmosphere.

In recent years, global atmospheric methane levels have increased erratically, sometimes by one percent per year.

Photo Lee Klinger, Copyright © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR)

View larger image View larger image |

|

| |

|

| |

|