|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Climate change reduces ocean food supply, threatening marine ecosystems |

8 December 2006In a NASA study, scientists have concluded that when Earth's climate warms, there is a reduction in the ocean's primary food supply. This poses a potential threat to fisheries and ecosystems. By comparing nearly a decade of global ocean satellite data with records of Earth's changing climate, scientists found that whenever climate temperatures warmed, marine plant life of microscopic phytoplankton declined. When temperatures cooled, marine plant life became more productive. The findings appear in the December 7th issue of the journal Nature. The results provide a preview of what could happen to ocean biology in the future if Earth's climate warms as the result of increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. |

Phytoplankton is plant life in the upper sunlit layer of the ocean, responsible for about the same amount of photosynthesis each year as all land plants combined. |

Phytoplankton is the essential plant life at the start of the marine food chain. Changes in photosynthesis and phytoplankton growth influence fishery yields, marine bird populations and the amount of carbon dioxide the oceans remove from the atmosphere. |

|

A close-up view of phytoplankton, the tiny plants that live in the sunlit upper layer of the ocean.Image NASA |

"The evidence is pretty clear that the Earth's climate is changing dramatically, and in this NASA research we see a specific consequence of that change," said oceanographer and study co-author Gene Carl Feldman of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. "It is only by understanding how climate and life on Earth are linked that we can realistically hope to predict how the Earth will be able to support life in the future." |

|

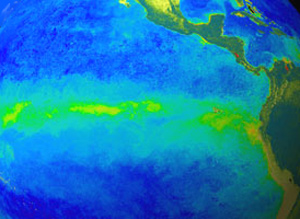

Above: Changes in phytoplankton change how much carbon dioxide the oceans remove from the atmosphere. The life cycle of phytoplankton in the ocean involves absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and nutrient-rich waters. That carbon is then passed on to higher life forms that feed on the plants. Some also sinks to the ocean floor. Image right: Satellite data reveals the ebb and flow of microscopic plant life in the world's ocean. In this late 1990s image of the Pacific, robust plant growth is shown in green; areas of low "productivity" are blue. Research has now shown how these marine plants are linked to changes in climate. |

|

|

On the Pacific coast of New Zealand, the advance of austral spring returns sunlight to spur phytoplankton blooms. This 2005 image shows a plume extending from the coast near Castlepoint in the southern North Island, and rotating in an offshore eddy. Another broader swath of less-intensely colored plankton appears in the lower part of the image. Large areas of plankton occur at 40° South latitude along the convergence zone known as the Subtropical Front, between the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and subtropical waters. The converging water masses mix and disperse nutrients with plankton blooms when spring lighting becomes strong enough. The zone extends east-west at the latitude of Cook Strait, and plankton in this image went east, past the Chatham Islands.

|

|

home | sponsors |

latest news & events |

join - donate |

contact information | projects |

UN delivers definitive warning on dangers of climate change

UN delivers definitive warning on dangers of climate change

View larger image

View larger image