|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Moas in decline before humans arrived

"Humans may not be entirely to blame for wiping out moas ... a huge moa population existed in the few thousand years before the arrival of humans ..."

New Scientist

10 November 2004

DNA shows female moa three times size of male

"The mystery of New Zealand's giant moa has been solved at last - she was a female"

New Zealand Herald

11 September 2003

New Zealand's flight path to disaster

"... New Zealand has a better record of the birds that lived over the past 100,000 years than any other area

of the world..."

New Zealand Herald

14 January 2003

Feathers to keep moa's toes warm

"Short, stocky and with feathers all the way down to its toes, the upland moa would have been an extraordinary sight ..."

New Zealand Herald

20 June 2002

Swamp yields moa haul in historic dig

"Palaeontologists working in North Canterbury will not know the extent of the biggest collection of swamp moa and other extinct or rare species until the end of the year."

New Zealand Herald

9 July 2001

Extinct bird in 'ground breaker'

"The DNA of extinct birds has shed new light on formation of Southern Hemisphere continents"

BBC NEWS

7 February 2001

|

|

|

| |

NEW ZEALAND ECOLOGY |

| |

|

|

FLIGHTLESS BIRDS |

| |

| |

The absence of mammalian predators and competitors in New Zealand, allowed dominant taxa to evolve from other animal groups that were functionally equal to mammals. With the exception of a few oceanic islands, they have no functional or taxonomic equivalent anywhere in the world.

Moa were the most significant alternative to mammals on New Zealand, taking the role of the largest dominant herbivores, the same role as large animals such as deer and elephants in other lands.

After 170 years of controversy over the evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa, research in 2009 identifies nine species, with three genera and six species in the Emeidae family, two Dinornis species in the Dinornithidae family, and one Megalapterygidae species.

Moa are the only species in the Dinornithiformes order, and together with New Zealand's iconic species, kiwi and tuatara, have endemic distinction at order level.

Moa were the dominant herbivore in the New Zealand ecosystem, and another biological peculiarity, which evolutionary scientists relate to the prolonged isolation, size, and geographical complexity of the country, and the scarcity of terrestrial mammals.

New Zealand is Earth's largest oceanic archipelago, and the most distant from any continental land mass, which together with a mixed topography, provided the conditions for natural selection processes that produced varied evolutionary outcomes. |

| |

|

| |

Extinct giant moa Dinornis robustus and D. novaezealandiae were the tallest birds on Earth - with the top of their back two metres above the ground. |

| |

|

| |

As Dr Jared Diamond of UCLA points out "... the only approach to moa elsewhere in the world were the elephant birds of Madagascar plus the surviving ratites of the continents, but none of these other groups of very large flightless herbivorous birds radiated to anything like the degree that the moas did ..."

Moa were part of the ratite group which diverged to isolated locations throughout the Pacific. They were a notable early group that have no ridge (keel) on their sternum (breast bone) to which wing muscles are attached in birds that fly.

Ratites are a basal lineage of birds that are hypothesized to have had a common ancestor 80 million years ago on the Cretaceous southern supercontinent of Gondwana, which subsequently underwent either vicarious speciation as the landmass fragmented, and/or flighted dispersal [Bunce, Worthy et.al 2009].

Living members of the ratite lineage include the ostrich of Africa, emu and cassowary of Australia and New Guinea, rhea of South America, and New Zealand kiwi. The extinct giant elephant bird of Madagascar, and fossil Sylvornis of New Caledonia were also ratites.

Morphological radiation of moa appears to have occurred much more recently than previous early Miocene (15 mya) estimates, and was coincident with the accelerated uplift of the Southern Alps just 5 to 8.5 mya [Bunce, Worthy et.al 2009].

Periodic bridging of the North and South Islands from lower sea level during glacial periods also influenced dispersal in the Pleistocene within the last 2 million years.

Together with recent fossil evidence, Bunce, Worthy, et.al suggest that the recent evolutionary history of nearly all of the iconic New Zealand terrestrial biota occurred principally on the South Island.

The absence of deep (20 million years) splits in the moa phylogeny suggest that all recent moa species originated from the southern landmass [Bunce, Worthy et.al 2009].

A new 5.8 mya estimate for the basal divergence of Megalapteryx correlates closely with the rapid phase of mountain uplift during the Miocene-Pliocene [Bunce, Worthy et.al 2009].

Other divergence estimates are 5.3 mya for the mean Dinornithidae/Emeidae taxon split, 1.45 mya for Dinornis, 1.9 mya for Pachyornis, 1.8 mya for Anomalopteryx/ Emeus plus Euryapteryx, and 1.35 mya for Emeus/Euryapteryx. |

| |

| |

|

| The tallest bird on Earth ..... |

| |

|

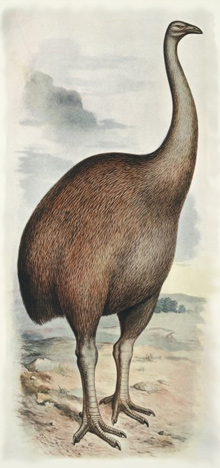

| The largest moa, the two female Dinornis species were the tallest birds on Earth - 6 feet tall at the top of their back. Paleoecologists no longer think the giant long necked moa normally stood erect (as shown right it would have reached 4 m [13 ft] in height). It is now thought that moa had a more horizontal neck posture, however, it could have reached up to 3 metres to graze on trees. Skeletal remains show that they were built like some dinosaurs.

A female Dinornis robustus weighed 275 kg (600 lb), less than the extinct elephant bird Aepyornis maximus of Madagascar that weighed 1100 lbs, but was much bigger than all other ratites. The largest living bird in the world today is the African ostrich which reaches a maximum weight of 114 kg (250 lb). Some individual Mantell's moa Pachyornis geranoides were a mere 17 kg, reaching up one metre, and with a back height of 0.5m, about the size of a large turkey. |

Image: Frederick William Frohawk 1861-1942, Dinornis ingens 1906. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa must be obtained before any re-use of this image. |

|

| |

|

| |

Moa were the only avian species in the world without any vestige of a wing. They also had no tail. The junction of a small scapulocoracoid bone, formed from the fused scapula and coracoid, is where the wing humerus was at an earlier evolutionary stage.

Formerly, morphological data defining the ratite family tree, suggested kiwi were closely related to moa by ten skeletal similarities. It was thought that kiwi and moa had the same ratite Gondwanan ancestor from which all ratites developed flightlessness, and co-existed but dispersed separately within New Zealand. |

| |

|

| |

Moa were the world's only avian species without any vestige of a wing. |

| |

|

| |

This supports the argument of arrival of moa and kiwi by a land connection prior to the late Cretaceous, before New Zealand broke off from Gondwana.

Genetic research has concluded that kiwi evolved from a Gondwana ancestor, that along with South American rhea and New Zealand moa diverged early in their evolution.

This places kiwi in the same group as Australia's emu and cassowary, and African ostrich, and probably flew to New Zealand about 40 million years ago.

Kiwi have vestigal wings, whereas moas had no wings whatsoever, indicating earlier divergence and the possibility of moa walking into New Zealand. Without ancient fossil evidence, the mystery of when moa became flightless, and how they reached New Zealand will be keenly debated.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Home > New Zealand ecology > Flightless birds > Moa |

| |

| |

|

| |

Right: Skull of Dinornis robustus.

Above: The upland moa Megalapteryx didinus was relatively small, weighing 14 to 63 kg. Bones have commonly been found in alpine areas, but it is also known to have occupied steep coastal areas of the South Island. It is the only moa with leg feathers down to its' ankles. Image by permission, Copyright © Peter Schouten. |

| |

|

| |

Reverse dimorphism - females much bigger than males .....

The extent of reverse sexual dimorphism in some moa is unprecedented among birds and terrestrial mammals with males smaller and different in shape than females.

Since the first moa was described in 1839, this led to confusion with as many as 64 species in 20 genera at one stage, and 38 listed by Walter Rothschild in Extinct birds in 1907.

At the time eleven moa species were recognised in 2003, three Dinornis species showed limited cladistic differences. Since Owen's description in 1839, the species had been separated primarilly on the basis of limb bone size.

The first sex-linked nuclear sequencing of an extinct species showed three morphological forms were one species, whose size was distinctly different according to sex and habitat.

The largest females of extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism were about 280% the weight and 150% the height of the largest males. [Bunce, Worthy, et.al, 2003]. Female Dinornis weighed between 80 and 275 kg, while males were only 40 to 90 kg.

The stout-legged moa Euryapteryx curtus was considered to be two species until recently, because of the difference of the female which weighed 40 to 105 kg, about the weight of an ostrich, and the turkey-sized male weighing between 12 and 34 kg.

Moa eggs were normally cream colored, however, some light green and teal blue shell has been found. The eggs of the biggest species were 24 centimetres (10 inches) long, and the largest egg that has been found has a capacity of 4,302 cubic centimetres (1.8 cubic feet), 100 times the capacity of an average sized chicken egg. |

| |

The fastest known extinction of a megafauna .....

The descendants of the original ratites proliferated and developed distinctively during millions of years of isolation on New Zealand, until the arrival of humans.

Moa had only one natural predator - the huge Haast's eagle Harpagornis moorei, the largest eagle ever known with a wing span of ten feet and talons as big as tiger's claws.

But life in a bird's paradise could not last, and after millions of years moas quickly ended up in Maori cooking pits, and much of their habitat was destroyed by fire.

Holdaway and Jacomb explored the impact on moa population of low exploitation levels by an initial population of 100 people, coupled with the habitat loss caused by them. Conservative analysis used low to medium human population growth rates, minimal rates of habitat removal in two areas of the two main islands, and the lowest cropping rates.

The total population of all species of moa at the time of human settlement was 158,000 birds, and only consumption of adult moas over one year old was considered. It is known that consumption of moa eggs was considerable, but was ignored in the study. |

| |

|

| |

"... human hunting and habitat destruction drove nine moa species to extinction less than 100 years after Polynesian settlement of New Zealand ..."

|

| |

|

| |

Moas, like most long-lived birds, were most vulnerable to any increase in adult mortality. When subjected to a low level of human predation, moas required an impossible increase in births to maintain their numbers.

Even without habitat loss that is known to have occured during the extinction period, the most conservative analysis suggests that moas were extinct within 160 years of human arrival.

Revised radiocarbon dating of charcoal in campsites, place the earliest arrival of moa hunters, Polynesians who were the ancestors of Maori, in the 13th century.

The archeological record clearly shows that moa bones were suddenly missing in campsites and Maori middens after the 14th century. The short period during which moa were eaten out of existence is a mere blink in the geological time of moa life.

In a commentary on the study, Dr Jared Diamond claims that in New Zealand, Madagascar and many Pacific Islands, few would deny that the first arriving humans caused mass extinction, and the only question is how fast it occurred and whether hunting was the only cause. He said the new study "shows that moa extinctions were very fast and were mainly by hunting".

Dr Ross MacPhee, a mammalogist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York who has studied ancient extinctions, says "there is no way of interpreting this record other than that it had to happen virtually overnight ... this is easily the best instance of overkill, of blitzkreig on record".

Moa extinction was more rapid than the rate of extermination of large prehistoric mammals such as mammoths, camels, ground sloths, mastodons and giant beavers that some scientists think was caused by hunters in a North American blitzkreig 13,000 years ago.

The predators that depended on these animals, which included saber-toothed cats, cheetahs, maned lions, wolves and short-faced bears are thought to have become extinct in 400 years. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Order: Dinornithiformes

Family: Emeidae

Eastern moa

Emeus crassus

Little bush moa (lesser moa)

Anomalopteryx didiformis

Crested moa

Pachyornis australis

Heavy-footed moa

Pachyornis elephantopus

Mantell's moa (Mappin's moa)

Pachyornis geranoides

Stout-legged moa

(Coastal moa)

Euryapteryx curtus

Family: Dinornithidae (Giant moa)

North Island giant moa

(Large bush moa)

Dinornis novaezealandiae

South Island giant moa

Dinornis robustus

Family: Megalapterygidae

Upland moa

Megalapteryx didinus

Did the ratite ancestor of moa walk or fly into New Zealand?

The tinamous group of South and Central America are not ratites but together with them are palaeognaths, one of two living super orders of birds.

Tinamous are quite different than moa - hen-sized flighted birds but poor fliers.

Mitochondrial DNA sequence [Phillips, et.al, 2010] research on the relationship of all palaeognaths, discovered that tinamous are not the cousins of the ratites, but fall within the ratite group, and are the closest relatives of moa.

Identification of tinamous within the flightless ratite group means that the ancestor of ratites could fly.

It is not known when ratites became flightless, and each lineage could have become flightless separately at different times, after dispersal in the separated pieces of the Gondwana continent.

The ancestor of moa could have flown to New Zealand, and then become flightless and much bigger, but this is still an open question.

References

Baker AJ, Huyen LJ, Haddrath O, Millar CD, Lambert DM; Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: the giant moas of New Zealand, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(23): 8257-8262, 31 May 2005.

Bunce M, Worthy TH, Ford T, Hoppitt W, Willerslev E, Drummond A, and Cooper A; Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis, Nature 425, 172-175, 11 September 2003.

Bunce M, Worthy TH, Phillips MJ, Holdaway RN, Willerslev E, Haile J, Shapiro B, Scofield P, Drummond A, Kamp PJJ, and Cooper A; The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 8 December 2009.

Holdaway RN, Jacomb C; Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications, Science Vol. 287 no. 5461 pp. 2250-2254, 24 March 2000.

Phillips MJ, Gibb GC, Crimp EA, Penny D; Tinamous and Moa flock together: Mitochondrial genome sequence analysis reveals independent losses of flight among ratites, Systematic Biology 2010, Vol 59 (1): pp 90-107.

Tennyson A, Martinson P; Extinct birds of New Zealand, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2006.

Worthy TH, Holdaway RN; The lost world of the moa: Prehistoric life of New Zealand, Indiana University Press, 2002. |

|

| |

|

|

|