| |

| |

|

| |

Explorers marvel at thriving brittlestar colony on a Macquarie Ridge seamount |

| |

19 May 2008

Scientists affiliated with the Census of Marine Life, exploring the secrets of the vast underwater Macquarie Ridge mountain range south of New Zealand, captured the first images of a unique brittlestar colony.

The rarely found species has thrived against daunting odds on the peak of a seamount – an underwater summit taller than the world’s tallest building.

Its cramped starfish-like inhabitants, tens of millions living arm tip to arm tip, owe their success to the seamount’s shape and to the swirling circumpolar current flowing over and around it at roughly four kilometers per hour.

The ocean current allows the underwater denizens to capture passing food simply by raising their arms, and it sweeps away fish and other hovering would-be predators. |

| |

|

|

| |

Oceans worldwide contain an estimated 100,000 seamounts rising at least one kilometre above the seabed, but fewer than 200 have been sampled in any detail. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Discovery of this marine metropolis, together with important new insights into seamount geology and physics, highlights a month-long expedition of the Macquarie Ridge aboard the research vessel Tangaroa of the National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research (NIWA), which has hosted the Census of Marine Life seamount program, CenSeam.

Formed at least 12.5 million years ago, Macquarie Ridge stretches 1,400 km south from New Zealand to just above the Antarctic Circle (see map below).

A multi-disciplinary scientific team from New Zealand and Australia extensively sampled this intriguing ecosystem deep beneath waves familiar to fishing trawlers but rarely reached by scientists.

Macquarie Ridge is one of a few places where the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is detoured in its endless clockwise churn at the globe’s southernmost latitudes – playing a vital part in the global ecosystem, merging and mixing waters of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Ocean.

Usually corals and sponges dominate seamount peaks, filtering food that arrives in the current. Biologists believe the discovery is the first dense aggregation of another filter feeder, the brittlestar, ever found atop a seamount,

The summit’s shape and extraordinary water current circumstances, 750-meters above the ocean floor, are thought to be the reasons for the dense agrregation.

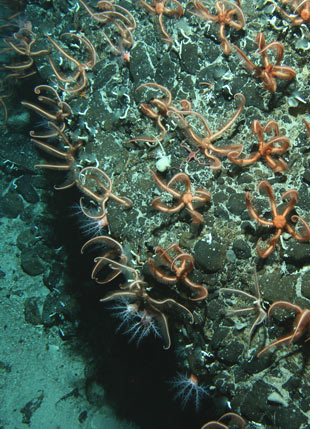

Hundreds of brown-black brittlestars covering each square meter were found. The scientists estimate that tens of millions of them populate the 100 sq.km flat top of the seamount.

“We were excited to see such a huge assemblage of brittlestars on the Macquarie Ridge seamount. Not only is it amazing to see a vast array of one type of organism but the implications of the find for our understanding of the relative uniqueness of seamount assemblages are potentially far-reaching.” said ecologist Dr Ashley Rowden of NIWA. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Above: The dots show the locations of seamounts along the Macquarie Ridge, stretching from the southerm tip of the South Island of New Zealand into the Southern Ocean. The New Zealand subantarctic islands, the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island, lie east of the Ridge, and Macquarie Island in the Australian Exclusive Economic Zone sits on top of it. Photo Copyright © NIWA 2008.

The Macquarie Ridge is on the Australian Plate, and together with the trench east of it on the Pacific Plate, defines the volcanically active Ring of Fire. The plate boundary extends northward through the earthquake prone Fiordland region on the west coast of the South Island, through the Southern Alps, the southern North Island, and then along the Kermadec Ridge northeast of the North Island.

Above right: A diverse assemblage of invertebrates including brittlestars, anemones, sponges and corals, and Calcererous algae on a Macquarie Ridge seamount. Photo Copyright © NIWA 2008

View slideshow of larger images View slideshow of larger images |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

Above: A seastar with its' arms raised to catch food in the current, together with corals and other invertebrates.

Photo Copyright © NIWA 2008

View larger image View larger image

Below: Part of a dense colony of brittlestar, probably Ophiacantha rosea, with soft corals, sponge and worms. Photo Copyright © NIWA 2008

View slideshow of larger images View slideshow of larger images |

|

| |

|

| |

Brittlestars are echinoderms, relatives of starfish, sea cucumbers, sea lilies and sea urchins.

Taxonomist Tim O’Hara of the Museum Victoria in Melbourne, Australia tentatively identified the smaller, densely packed brown-black brittlestar species found on the sand and cobble substrate of the peak, as Ophiacantha otagoensis or Ophiacantha fidelis.

Larger orange-red species found down the seamount’s flanks, with waving arms in the current to collect passing food, were tentatively identified as Ophiacantha rosea.

Thousands of specimens were gathered from eight seamounts. Full identification may take many years. The biologists believe some species have never been recorded before in the region, and some may be new to science.

An abundance of Epigonus species of deepwater cardinal fish was found sheltering below a rock ledge on the seamount, where they could conserve energy and access food.

Several Morid cods of the family Moridae were found in the folds of a large bubblegum coral which was nearly two meters high and hundreds of years old. These fish were also believed to be finding shelter from the current and perhaps benefiting in other ways from their close association with the coral. |

| |

|

| |

Seamounts can be highly productive and biodiverse, and serve as feeding grounds for fish, marine mammals and seabirds. They may also be important way stations for marine migrations. |

|

| |

|

| |

The Brittlestar seamount has several geological faults affecting its shape and geomorphology. The odd rectangular edge of its southern peak was formed by the intersection of two perpendicular faults.

Because the upper surface is relatively flat, experts believe it was once at sea level, or slightly submerged. The flat topography suggests wave erosion occurred during the last ice age 18,000 years ago, when sea level was low. The base of the seamount is 850 meters below the surface, and the peak is 90 meters underwater. |

|

| |

|

| |

The water mass of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current passing over the top and through ridge gaps of the seamount, moving at 2 knots (about 4 km/hour), is estimated to be 110 to 150 times larger than all the water flowing in all the rivers of the world. According to Dr Mike Williams of NIWA, New Zealand sits right beside the motorway of the world's oceans.

The Macquarie Ridge creates a strategic marine junction. “Understanding this current will shed light on how much water flows into the Pacific instead of continuing to circumnavigate Antarctica. This is important for understanding and predicting the impact of potential changes in the current on climate throughout the Southwest Pacific.”

Data was collected from nine strings of metering instruments, anchored a year earlier in two gaps or "choke points" in the Ridge, through which the current squeezes. It was astonishing to find that the current had pushed the top instruments on some strings down one kilometer below the surface.

|

| |

|

| |

|